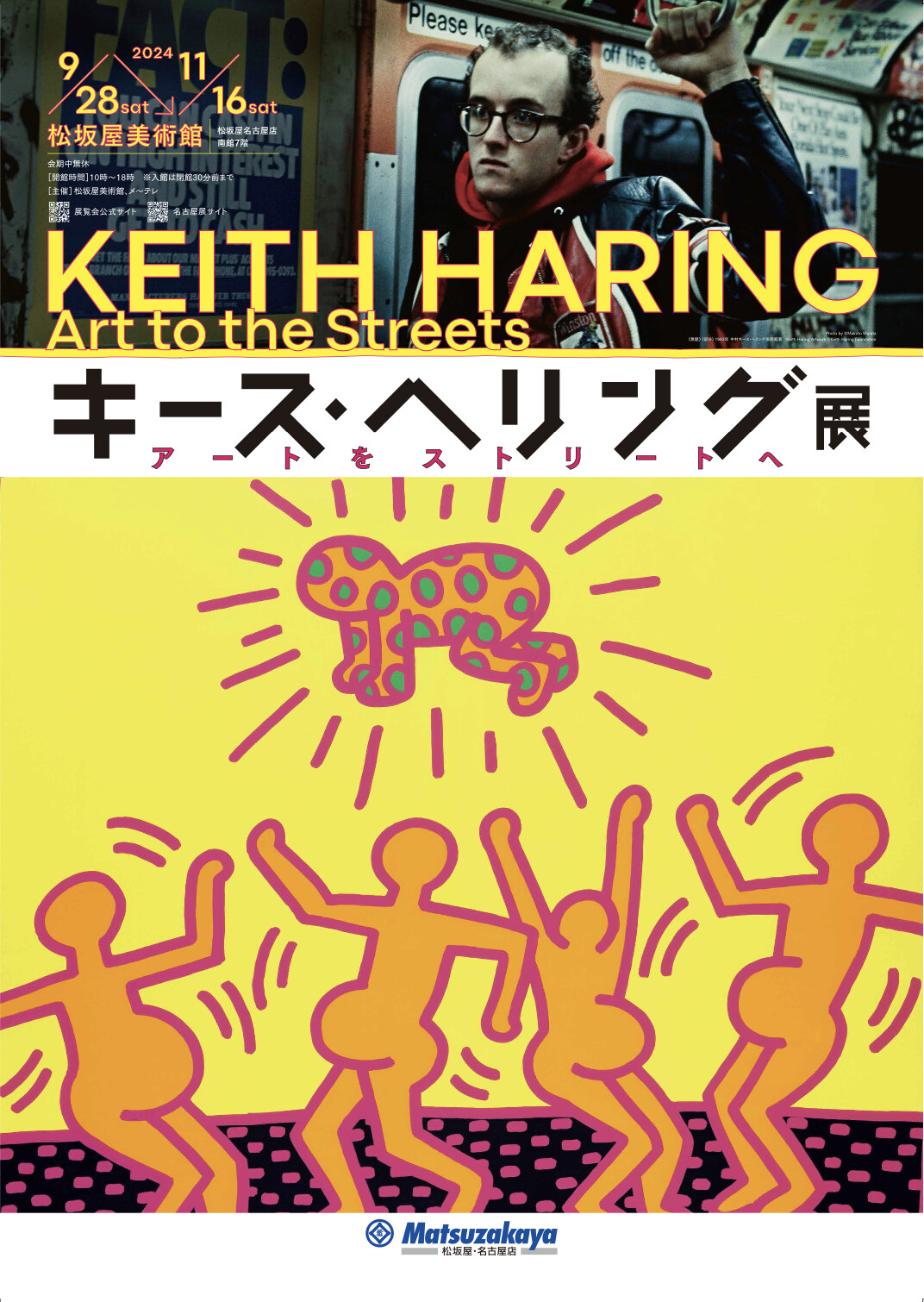

Keith Haring: Art to the Streets

Organized by Matsuzakaya Museum, Nagoya Broadcasting Network Co., Ltd.

With the special cooperation of Nakamura Keith Haring Collection

With the cooperation of PIA Corporation

With the planning of The Asahi Shimbun, TOEI COMPANY, LTD.

Mori Arts Center Gallery

December 9, 2023 – February 25, 2024

Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art

April 27, 2024 – June 23, 2024

Fukuoka Art Museum

July 13, 2024 – September 8, 2024

Shizuoka City Museum of Art

November 28, 2024 – January 19, 2025

The Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

February 1, 2025 – April 6, 2025

Keith Haring: Art to the Streets is a large-scale touring exhibition of Keith Haring, a renowned American artist of the 1980s known for his bright pop imagery, that is held at Matsuzakaya Art Museum.

Based on the belief that “art is for everybody”, Haring disseminated his work throughout everyday life using the subway and streets based mainly in New York. In this way, he gave everyone the opportunity to encounter art. Moreover, in an era predating the internet and social media, Haring conveyed strong social messages to a chaotic society through his works. This made a pioneering figure in the effort to expand the potential of an art-based dialogue with the general public. During his fast-paced 31-year life, Haring spent roughly a decade working as an artist. However, his impressive works, distinguished by their simple bold lines, are still loved by people all over the world, inspiring collaborations in a host of different genres.

This exhibition presents a comprehensive collection of approximately 150 pieces, including the subway drawings that made Haring’s name to monumental, a six-meter-long work and important materials detailing the artist’s special link to Japan. Haring’s art, which he used to fight against latent social violence and inequality, and discrimination and lack of government support for HIV/AIDS community until the end of his life, transcends both time and space, retaining the power to touch our hearts even today.

HIGHLIGHTS

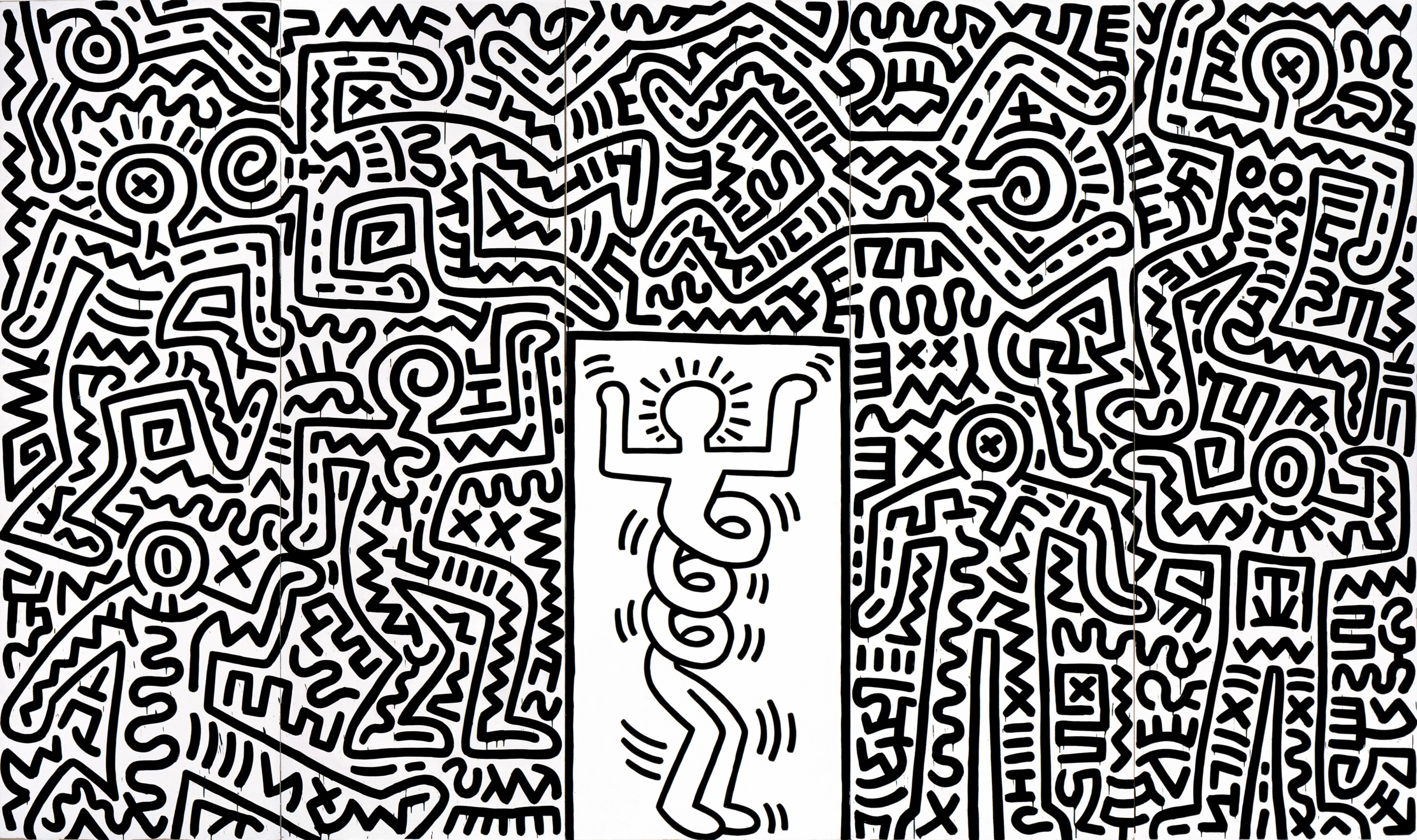

1. Art in Transit

In 1978, after moving from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to New York City and enrolling at the School of Visual Arts, Haring explored a wide range of artistic expressions, including painting, video, and installation art. While studying, he sought ways to bring art into public spaces beyond traditional exhibition venues like museums and galleries.

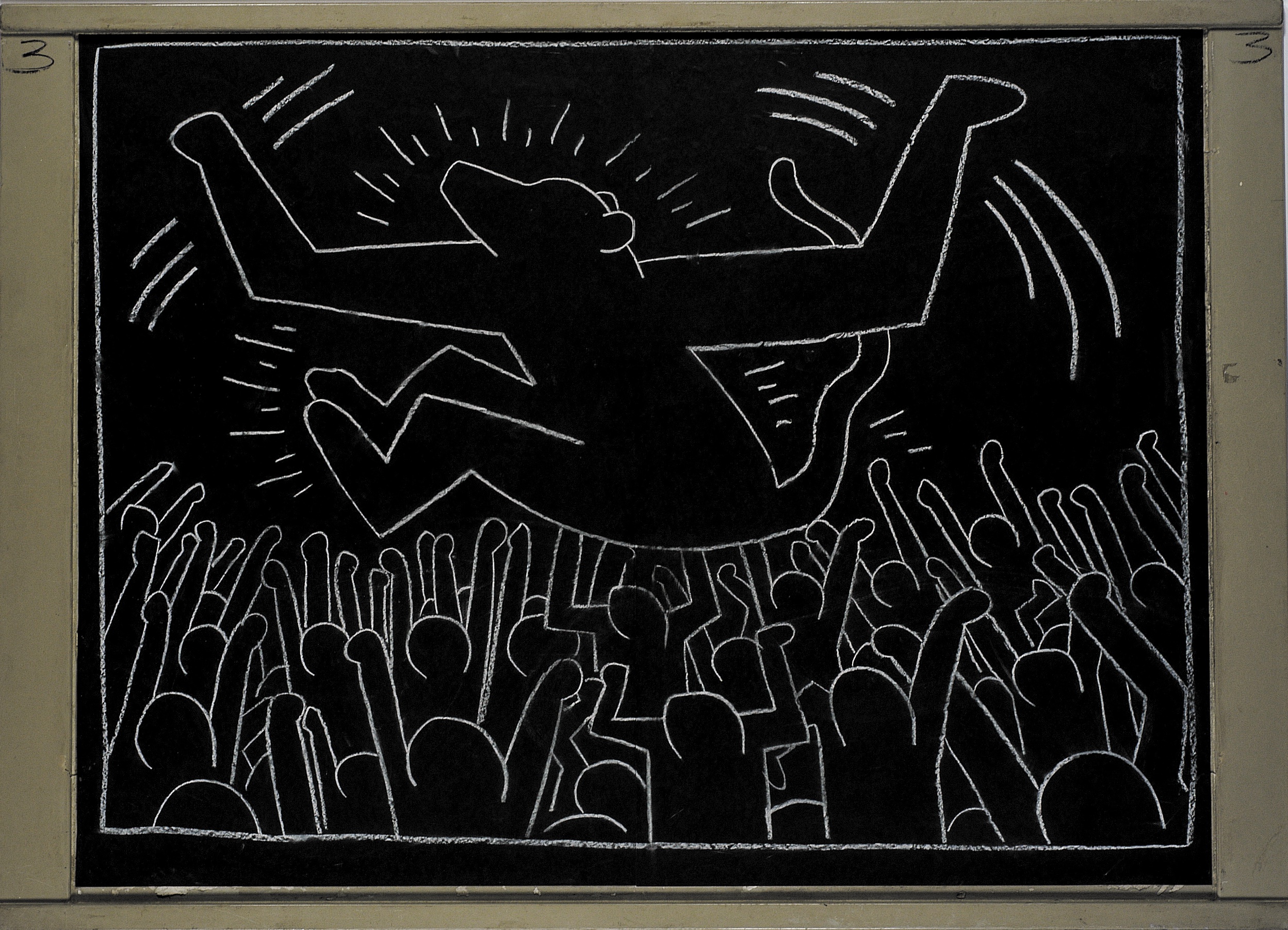

Among these efforts, he focused on the subway, a space used by people of all races, classes, genders, and occupations. “If I draw here, everyone will see my work,” he thought. He began creating chalk drawings on the blank black paper covering unused advertising panels in subway stations. His simple, quickly sketched images—radiant babies, barking dogs, and spaceships emitting rays of light—captivated the hearts and minds of countless New Yorkers.

2. Life and Labyrinth

As HIV began to cast a dark shadow over society, New York City offered an exhilarating environment for Haring, a young artist from rural Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The city’s vibrant gay culture was a stark contrast to his upbringing and provided a sense of liberation. Immersed in the chaos and hope of New York, Haring channeled his energy into the city, balancing the joy of life with the looming fear of death during a creative journey that spanned just over a decade.

Influenced by Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Alechinsky, William Burroughs, and Robert Henri’s manifesto The Art Spirit, which championed artistic independence, Haring developed his unique style. He also incorporated elements inspired by African art into his work, further refining his artistic identity.

“Life is so fragile. It is a very fine line between life and death. I realize I am walking this line. Living in New York City and also flying on airplanes so much, I face the possibility of death every day.” he reflected on July 7, 1986.

3. Pop Art and Culture

In the 1980s, under the shadow of a struggling U.S. economy, New York City was notorious for its high crime rates, far worse than today, and was plagued by drugs, violence, and poverty. Yet, the city pulsed with energy as the club scene flourished, street art reached its zenith, and culture thrived. Iconic works by Andy Warhol, Madonna, and Jean-Michel Basquiat emerged from this vibrant yet chaotic environment. Writers like William S. Burroughs, poets and critics like Allen Ginsberg, supermodels, celebrities, and musicians all frequented the city’s clubs, while young artists fiercely sought opportunities to showcase their talents outside traditional galleries and theaters.

Among these, Paradise Garage stood out as a cultural melting pot. For Haring, it was not just the ultimate club—home to the legendary DJ Larry Levan and electrifying dance floors—but also a sacred space where music, dance, and creativity intertwined to inspire his artistic vision.

In this era of cultural convergence, Haring expanded his practice beyond pop art, collaborating with performing arts, advertising, and music, and finding inspiration in the dynamic interplay of these creative realms.

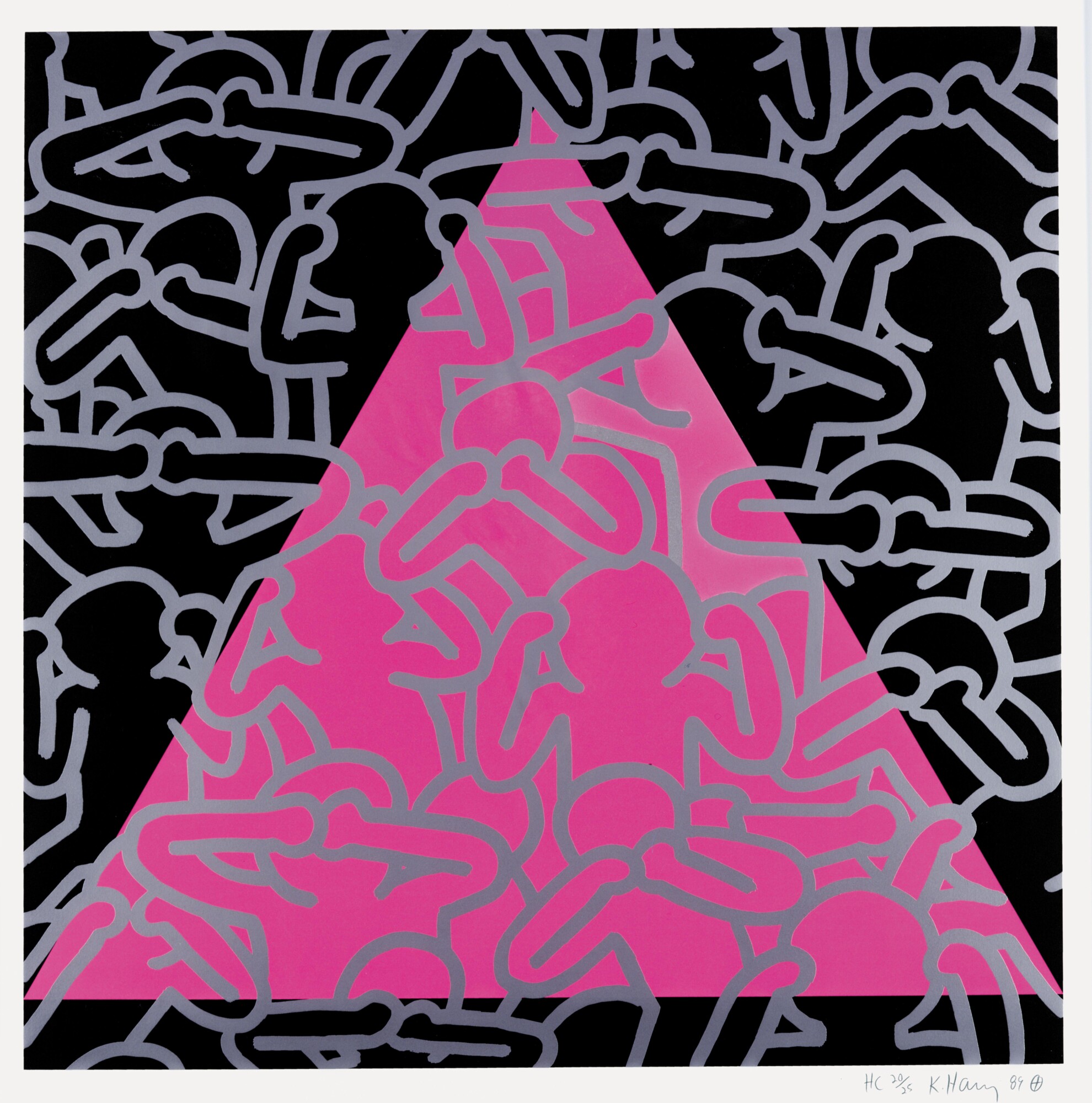

4. Art Activism

Keith Haring used posters as a medium to communicate his messages directly to the public. His poster designs encompassed a wide range of themes, from socially conscious topics such as nuclear disarmament, anti-apartheid, AIDS awareness, and celebrating sexual minorities on National Coming Out Day, to commercial collaborations with brands like Absolut Vodka and Swatch. In total, he created over 100 posters.

Among these, many carried strong social messages. The first poster Haring ever created was for nuclear disarmament. Self-financed in 1982, he printed 20,000 copies and distributed them for free during a massive protest in Central Park against nuclear weapons and the arms race.

Believing in the power of art to inspire and promote peace, Haring extended his efforts beyond posters. He engaged in workshops with children, painted murals, and used various mediums to convey his vision for a better world.

5. Art is for Everybody

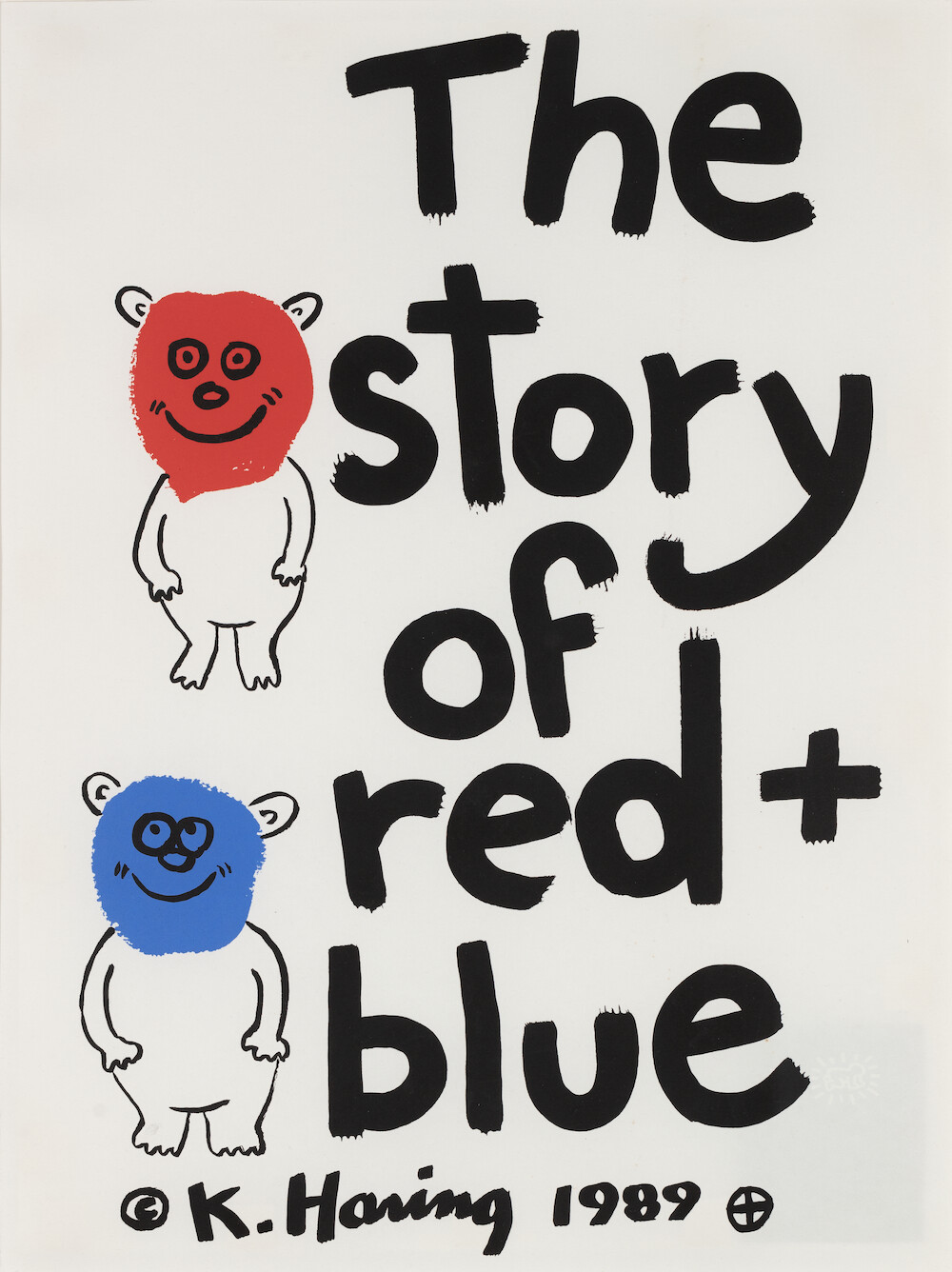

Haring sought to make art accessible not just to the wealthy but to the wider public. Beginning with his activities in the streets and subway stations, he fostered communication with the masses through various art initiatives, including his Pop Shop, where he sold products featuring his designs.

A central work of this chapter, The Story of Red and Blue, exemplifies Haring’s use of visual language to create a narrative through a series of paintings, appealing not only to children but also to adults. His sculptures, crafted with primary colors like red, yellow, and blue, and transforming flat shapes into three-dimensional forms, embody simplicity and the ability to communicate universally.

Haring created public art—including sculptures and murals—in dozens of cities worldwide, much of it as part of charitable efforts for children. His legacy continues to reach the public through numerous published picture books, which remain beloved to this day, ensuring his art lives on as a gift to all.

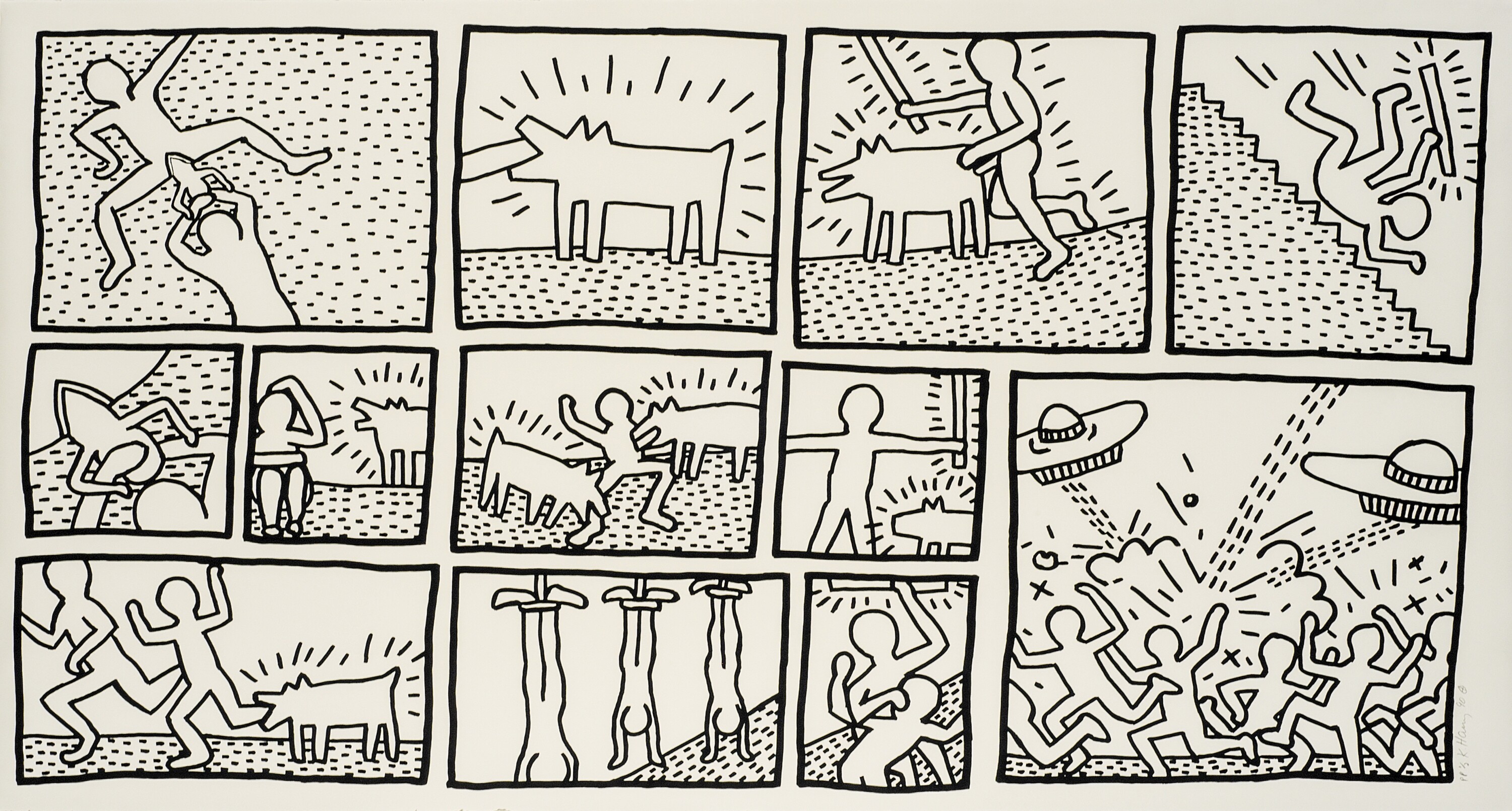

6. Present to Future

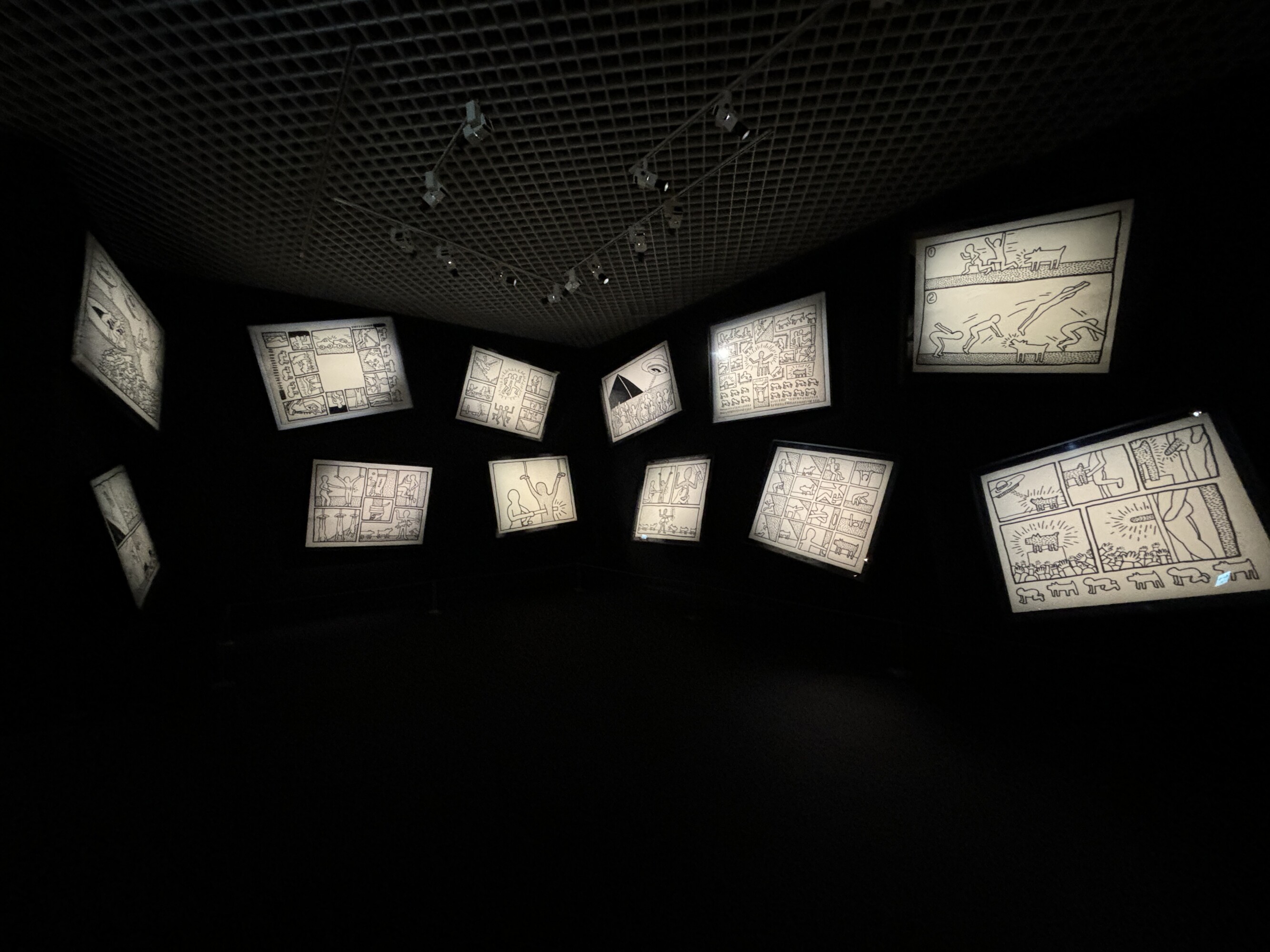

Haring described the 17-piece Blueprint Drawings as a “time capsule revealing the beginnings in New York.” While each piece is presented without accompanying explanations, the series depicts, in monochrome and with a comic-like simplicity, a society plagued by inequality, conflict, and the chaos of capitalism, as well as a future where technology dominates humanity. As with many of Haring’s works, this series invites viewers to confront the pieces, reflect on their own realities, and derive personal meaning.

Similarly, his monumental Untitled, showcased in his final solo exhibition, and the iconic Radiant Baby from Icons—the glowing figure beloved worldwide—generate interpretations as diverse as the viewers themselves. Haring’s vision, depicting the present as the future and the future as the present, continues to resonate even more than 30 years after his passing, traveling through time as part of history itself.

Special Topic: Keith Haring and Japan

Haring’s first visit to Japan, a country for which he held a deep affection, was over 40 years ago in 1983. Even before this trip, he had been influenced by Eastern philosophy and traditional calligraphy. During his visit, he created ink drawings on uniquely Japanese items such as folding fans and hanging scrolls. At the time, Tokyo, buoyed by the economic bubble, appeared to Haring as an exotic city where futuristic innovation and traditional culture harmoniously coexisted.

In 1987, Haring collaborated with approximately 500 children on a large-scale mural at Parthenon Tama in Tama City, Tokyo. The following year, in 1988, he opened Pop Shop Tokyo in Aoyama, selling merchandise he had designed, which garnered significant attention. Pop Shop Tokyo offered T-shirts, buttons, posters, magnets, toys, and other items, creating a new network where art was accessible to everyone. The shop also produced numerous items that fused Japanese cultural elements with Haring’s art, including bowls and fans, many of which are featured in this exhibition.

In the same year, despite his hectic schedule, Haring visited Hiroshima. There, he designed the poster for a concert titled Of Course We Want Peace!!, held at the Hiroshima Sun Plaza Hall.

INSTALLATION VIEW

FEATURED ARTWORKS